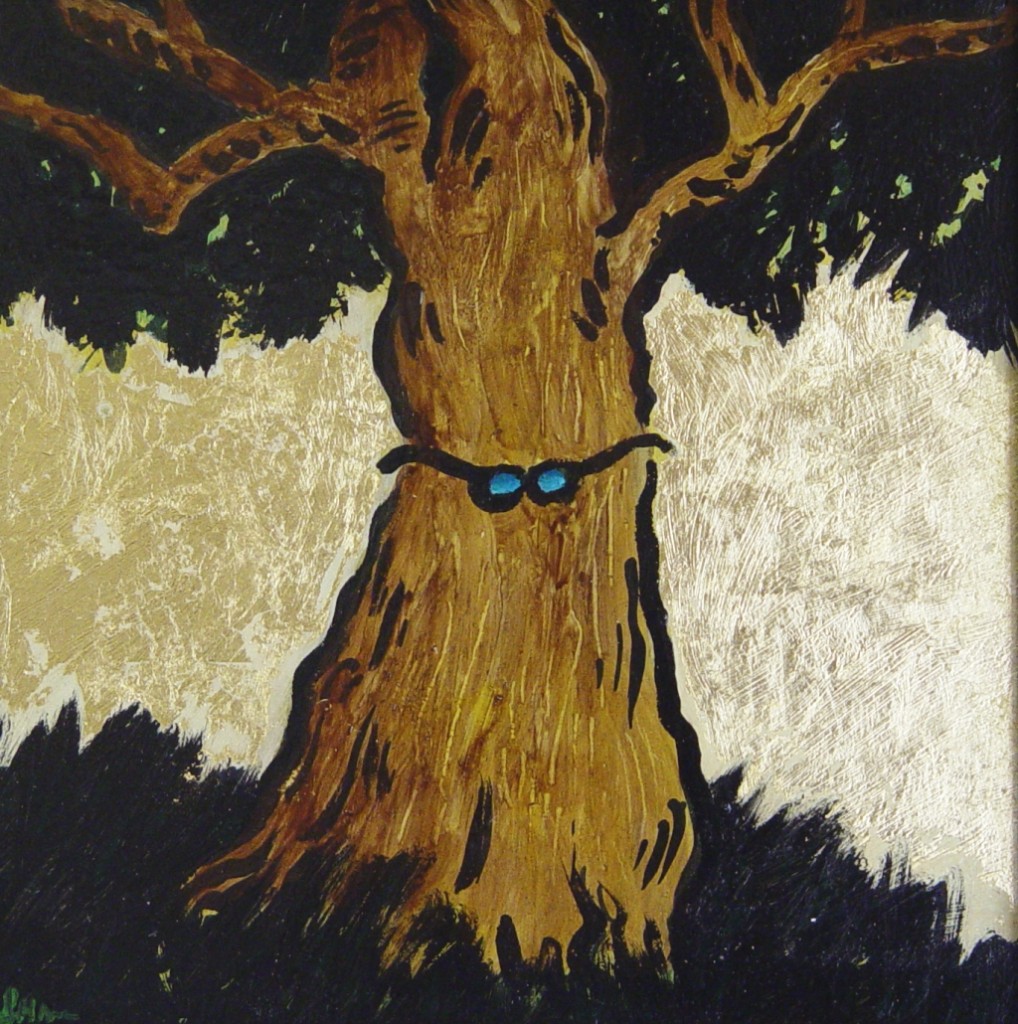

The natural world is full of surprises. Trees, for example. At the end of its first year’s growth, an apple tree has already made 17 million root hairs, with a total length of about 2 kilometres. These root hairs are not just passive filaments absorbing water and minerals. They react to the environment; they have sensitivity, and can move. They develop relationships with other organisms, such as micorrhizal fungi, which extend their own microscopic roots around and into the cells of the root hairs, supplying the tree with substances that otherwise they wouldn’t be able to absorb so efficiently. Trees can communicate with each other: if two roots of the same species grow next to each other, they can actually graft together, and so can transmit infection – or resistance to infection – from one tree to another. The root area of a tree can be up to seven times the surface area of the crown of the tree, so in a forest, trees link with many others around them, communicating by means of exudates and plant hormones. The electrical impulses that are characteristic of an animal’s nerve cells can also be found in trees, so that the entire plant almost instantly receives information about something that has happened in just one part of it. Research in this field has become a new field, plant neurobiology. To simplify drastically, a tree is an organism with its ‘head’ in the soil. And a forest? It’s like a crowd of people, all embracing while they’re doing their own thing. Who knows what they’re thinking.

La natura è piena di sorprese. Prendiamo ad esempio un albero, dopo soltanto un anno dalla sua germinazione, ha già sviluppato 17 milioni di filamenti radicali con una lunghezza complessiva di due kilometri. I filamenti non sono strutture passive: assorbono acqua e minerali, possiedono una particolare sensibilità ai diversi stimoli ambientali, e possono reagire con il movimento. Sviluppano rapporti con altri organismi quali i fungi micorriziche che nutrono l’albero con certi minerali che altrimenti non riuscirebbero ad assorbire. Le radici degli alberi possono interagire tra di loro, riconoscendo quelli di un altro albero della stessa specie fino a fondersi, stabilendo una comunicazione tramite la quale possono passarsi informazioni su come resistere a infezioni patologiche.

Considerando che l’area del terreno colonizzato dalle radici di un albero può essere sette volte l’area della chioma, è evidente che un albero in una foresta riesce a stabilire una fitta rete di contatti con i suoi vicini, comunicando con fitormoni ma anche con impulsi elettrici. Le potenziali elettriche, tipiche dei neuroni animali, si trovano anche nelle cellule delle piante. La ricerca scientifica in questo campo è diventata una nuova disciplina, la neurobiologia vegetale. In sintesi, se l’albero è un organismo con la ‘testa’ nel terreno, la foresta che cos’è? E’ una folla immensa di persone che vivono la loro vita abbracciate per sempre. Chissà a cosa stanno pensando.